Why does Ukraine need the Istanbul Convention?

One of the international treaties around which numerous myths and stereotypes have been born, and manipulations have continued, is the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (hereinafter referred to as the Istanbul Convention).

In my opinion, this is due to the fact that this document is valuable and holistic. It contains norms that oblige states to review established practices in combating violence against women and domestic violence, and primarily to eradicate gender stereotypes. After all, stereotypes about the “desirable” or “acceptable” behavior of a woman or a man in Ukrainian society are not just harmful, but also lead to tolerance of violence and human rights violations against those who, in our opinion, behave “not in accordance with the rules”, or against those who have less power, protection opportunities, etc.

In her book “How to Understand Ukrainians: A Cross-Cultural Perspective,” Maryna Starodubska explores our national mentality, culture, and values, which explain our attitude and perception of certain processes in the country. The author notes that at the personal level, the most important value for Ukrainians is freedom (83.9%), but at the same time, justice (72.5%) is lower than freedom, and the demand for dignity (60.4%) and equality (56.5%) is decreasing from year to year.

“It is not surprising that under such conditions, it is so difficult for people from different communities (we often call them “bubbles”) to negotiate, because everyone strives for maximum freedom of choice and benefit for themselves and does not think about its fairness or accessibility for others.”

We have gone through this path of heated discussions, debunking myths, and have come to the conclusion that we still need to ratify the Istanbul Convention, because the country really lacks tools to combat domestic violence and violence against women.

We have faced new challenges generated by Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine; after all, we are the ones confidently moving towards the EU, and therefore, we must not only bring our legislation into line, but also work to systematically change approaches to working with victims of gender-based violence in practice.

I started working with victims of domestic violence in 2007. At that time, we had the old Law of Ukraine “On the Prevention of Domestic Violence” in force. The practice of applying this law has shown that we do not have enough tools to respond to violence, that the very concept of “domestic violence” significantly limits the circle of persons who can be held accountable.

For example, at that time, it was impossible to hold a former husband or wife, who did not live together and did not have a common life, liable for violence, since this was not included in the definition of “family” within the meaning of the Family Code of Ukraine. There were also no tools to isolate the abuser from the victim. Law enforcement agencies often complained about the insufficiency of mechanisms for stopping violence and removing the abuser, the ineffectiveness of existing administrative measures, etc. Until 2017, there was no such crime as “domestic violence” in the Criminal Code of Ukraine. And if the victim did not suffer any physical injuries, the abuser could only be held administratively liable, even if the violence had lasted for years.

In 2016, there was an attempt to ratify the Istanbul Convention and, in parallel, to adopt a new Law of Ukraine “On Prevention and Combating Domestic Violence” and make relevant amendments to the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

The Convention was not ratified, but the law was adopted and in parallel with this, amendments were made to the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

So, since 2017, the Law of Ukraine “On Prevention and Counteraction to Domestic Violence” has been in force in our country, Article 126-1 Domestic Violence has appeared in the Criminal Code of Ukraine, as well as in Articles 152 of the Criminal Code and 153 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which relate to sexual violence, the concept of “voluntary consent” has been introduced, the absence of which means that rape or sexual violence not related to penetration of the person’s body has been committed.

It is also very important that in the case of committing any crime against a spouse or ex-spouse or another person with whom the perpetrator is (was) in a family or close relationship, this will be considered an aggravating circumstance, which gives the court the right to apply a more severe punishment.

Thus, Ukrainian society has changed its approach to investigating domestic violence cases at the legislative level, which have become crimes, not just administrative offenses.

It would seem that why should we ratify the Istanbul Convention, if we have already adopted a new law, made amendments to the Criminal Code and can work without the Convention.

However, this turned out to be not enough. In practice, problems began to arise with the investigation of domestic violence cases, while we have not learned to identify and investigate sexual violence, because it is difficult for us to understand what the concept of “voluntary consent” is.

And here we return to the fact that Istanbul The Istanbul Convention is a valuable and holistic document. A system aimed only at applying a formal approach cannot work. It is not enough to adopt a law.

It is important for us to understand the spirit of the Istanbul Convention, because it is not for nothing that it speaks of a comprehensive, systemic and coordinated approach to combating violence against women and domestic violence.

The 4P formula, embedded in the content of the Istanbul Convention:

Prevention

Protection

Prosecution

Coordination policies

All these four areas must develop in parallel, otherwise we will not achieve results.

Regarding values and understanding of the problem, the Istanbul Convention outlines in its preamble the main roots and deep understanding of the phenomenon of violence against women and domestic violence, namely emphasizing:

the realization of de jure and de facto equality between women and men is a key element in preventing violence against women;

violence against women is a manifestation of the historically unequal balance of power between women and men, which has led to the domination of women and discrimination against women by men and to the prevention of the full emancipation of women;

the structural nature of violence against women as gender-based violence, as well as the fact that violence against women is one of the main social mechanisms through which women are forced to occupy a subordinate position compared to men.

Joining the states that strive to “create a Europe free from violence against women and domestic violence”, in June 2022 the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine voted to ratify the Istanbul Convention.

This important document was adopted in the year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It is worth noting that in its preamble, the Convention emphasizes that states, by ratifying it, recognize “the ongoing human rights violations during armed conflicts that affect the civilian population, especially women, in the form of widespread or systematic rape and sexual violence, as well as the possibility of an increase in gender-based violence both during and after conflicts” and, in this regard, agreed to implement measures to prevent, protect and prosecute such crimes and to build a coordinated policy.

Implementation of the Istanbul Convention: the state of affairs at the beginning of 2025

Despite the full-scale war, work on the implementation of the norms of the Istanbul Convention continues. All key parties, namely the Government, Parliament and civil society organizations, continued to work on the analysis and amendments to the legislation and, in parallel, on changing the approaches in the work of all responsible entities.

It is important to note that the time since the adoption of the Law of Ukraine “On Prevention and Combating Domestic Violence” (2017), the amendments to the Criminal Code of Ukraine in the area of domestic and sexual violence have shown us to this day what gaps have arisen in terms of application practice and what is important to take into account both in the work on bringing the legislation into line and in the work on forming approaches in practice.

It is necessary to realize and understand that laws are living documents that are polished by the practice of their application.

Since the ratification of the Istanbul Convention to this day, there have been a number of legislative and other initiatives aimed at implementing the norms. I will mention some of them in this publication, on which the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the National Police of Ukraine, a number of deputies, including Maryna Bardina, Inna Sovsun, the NGO “La Strada — Ukraine”, the Association of Women Lawyers of Ukraine “YurFem”, the judicial and scientific communities worked.

On December 19, 2024, the Law of Ukraine “On Amendments to the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offenses and Other Laws of Ukraine in Connection with the Ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence” came into force.

We can highlight the following changes introduced by this law:

Article 173-7 of the Code of Administrative Offenses provides for administrative liability for sexual harassment, including in the field of electronic communications, as well as in relation to a person who is in material, official or other dependence. Before the adoption of this law, there was no separate article in the legislation of Ukraine on liability specifically for sexual harassment. In practice, such actions were classified as gender-based violence in the Code of Administrative Offenses or as sexual violence in accordance with Article 153 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

Gender-based violence has been removed to a separate article 173-6 of the Code of Administrative Offenses. So, we now have Article 173-2 Perpetration of domestic violence and a separate article on gender-based violence. This makes it possible to correctly qualify and collect data on the commission of an offense.

Separately, Article 269 of the Code of Administrative Offenses emphasizes that if “domestic violence and gender-based violence were committed in the presence of a minor or underage person, such a person is also recognized as a victim, regardless of whether the damage caused by such an offense, and it is subject to the rights of the victim, except for the right to compensation for property damage.

Also, on December 19, 2024, the Law of Ukraine “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving the Mechanism for Preventing and Counteracting Domestic Violence and Gender-Based Violence” came into force.

Among the many important provisions of this regulatory document, I would like to highlight the amendments to the Family Code of Ukraine, namely to Articles 110 and 111, which give the right to apply to the court with an application for divorce during the wife’s pregnancy and in the event of a child under one year old, and also prohibit the court from applying reconciliation during divorce in cases of domestic violence.

It would seem that very simple norms on the most important principle of “voluntariness of marriage”, but at the same time extremely strong resistance from the legal community, including from the side.

Before the adoption of these changes, spouses (either only the husband or only the wife) could not even apply to the court with an application for divorce if the wife was pregnant or had a child under one year old. If such an application was filed, the court refused to open proceedings on formal grounds. That is, in fact, the husband and wife lost the right to access justice. And what is more important, in the case of domestic violence, it was the perpetrator, who tried to keep the victim under control, who used this norm as one of the ways to make it impossible to dissolve the marriage, and therefore, to depend on him.

And, of course, abuse of the right to reconciliation was also often used by the perpetrator as a way to put pressure on the victim, so in view of this, in the case of divorce in the presence of domestic violence, such reconciliation cannot be applied.

Of extreme importance is the draft law, registered on December 9, 2024, No. 12297 “On Amendments to the Criminal and Criminal Procedure Codes of Ukraine to Ensure the Full Implementation of the Provisions of International Law on Combating Domestic and Other Types of Violence, Including Against Children”.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, the National Police, JurFem and La Strada have been working on this draft law since 2022. The draft law covers a wide range of issues that need to be resolved in view of the challenges that exist in practice and the requirements of the Istanbul Convention.

The draft law, in particular, proposes to resolve the following important issues:

To define the concept of “criminal offense related to domestic violence”. Yes, since 2017, our Criminal Code has provided for a separate article on the commission of domestic violence (Article 126-1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), but this is not the only article under which one can be held criminally liable for domestic violence. For example, the perpetrator may inflict bodily harm on the victim for the first time or commit beatings or torture, or other crimes that will be related specifically to domestic violence and liability for which will be provided for in other articles of the Code. Therefore, in order to emphasize the commission of crimes related to domestic violence, it is important to provide for the concept of “criminal offense related to domestic violence” in the Criminal Code. This is important not only for statistics, but also for the rights of the victim and avoiding pressure from the perpetrator, who will try to force the victim to close the case. After the innovations, it will be impossible to close a case when a criminal offense related to domestic violence occurs, even if the victim refuses to file a statement.

Explain what should be understood by the “systematic commission of domestic violence”, which gives grounds to talk about criminal liability. After all, in practice, different interpretations of systematicity have arisen.

It is very important that this draft law proposes to provide for criminal liability for stalking, namely, intentional, twice or more illegal surveillance, imposition of communication, other illegal direct or indirect intrusion in any way into the personal or family life of the victim against their will, including using electronic communications, which causes them to fear for the safety of their life or the health of their loved ones.

Special attention in the draft law is paid to the use of restrictive measures in cases not only regarding domestic violence, but also sexual violence.

An extremely important issue, which has already been tried to be regulated by other draft laws, is the exclusion of cases of domestic violence, rape, sexual violence from the list of cases of private prosecution. This means that it is not necessary to place responsibility on the victim for initiating criminal proceedings by means of a corresponding appeal. This will mean that if law enforcement officers become aware of such crimes from any sources or from any persons, they are obliged to initiate criminal proceedings and investigate them.

From the moment of registration of the draft law to the time of its adoption, as practice shows, it can change significantly: some norms can will be removed, and others will be added. However, in its current form, this bill addresses a significant range of issues that arise in practice and are extremely necessary for effective protection and investigation of cases of domestic and sexual violence.

On February 4, 2025, the Committee of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine on the Integration of Ukraine into the European Union issued its conclusion, according to which this bill meets the requirements of the Istanbul Convention, does not contradict EU law and international obligations in the field of European integration.

What still needs to be done

Two and a half years since the ratification of the Istanbul Convention, significant steps have been taken to implement it in wartime. Of course, much work remains to be done both at the legislative level and in practical implementation.

Regulatory documents are the basis, but they are applied by people working in law enforcement, judicial, social spheres, public organizations, etc. Therefore, in parallel with legislative initiatives, it is necessary to implement victim-centered approaches, especially to ensure the localization of those approaches and documents that have been formed at the national level.

Comprehensive assistance to the victim, avoidance of re-traumatization, communication with society and destruction of stereotypes that lead to victimization and stigmatization of victims are what we need to work with.

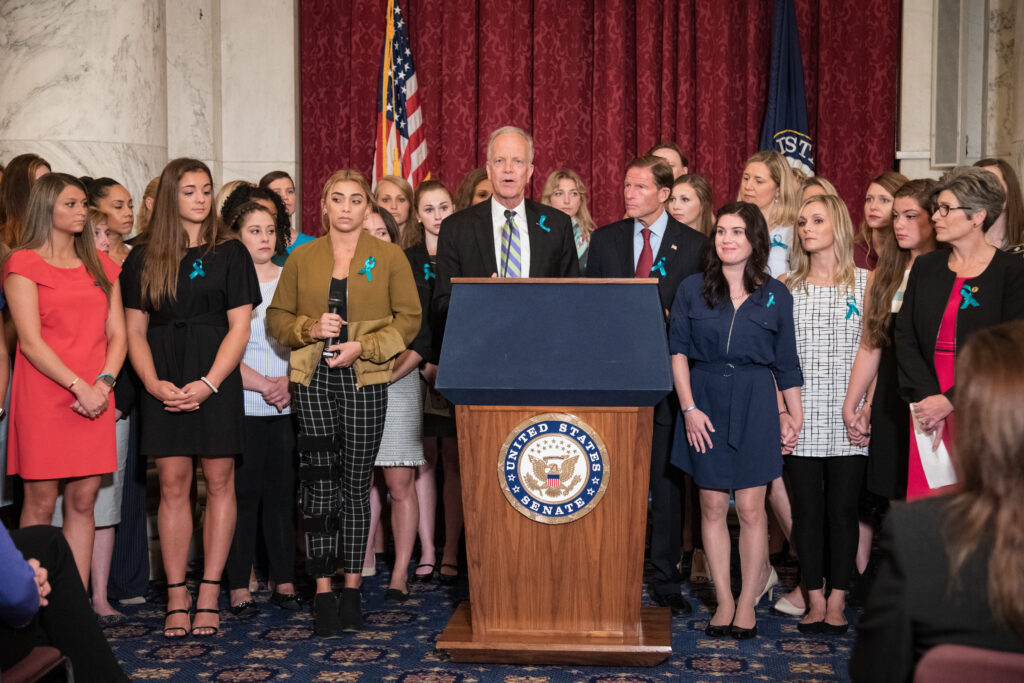

For the past two years, JurFem, in partnership with the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the National Police, with the participation of the Ministry of Social Policy and the Free Legal Aid System and public organizations, has been holding an annual conference “Justice Focused on Victims of Gender-Based Violence”. Based on its results, we always form the next steps together with the community. In particular, in 2023, we set ourselves the task of preparing, together with the UCP, standards for pre-trial investigation of domestic violence cases using victim-centered approaches. Such standards were prepared and presented to the community at a conference in November 2024.

In addition, three blocks of recommendations were identified that outline our next steps.

The first block is the issue of institutional changes. During one of the workshops, Judge Vira Levko noted that initiatives are based on individual people, but it is important to build institutional memory, strengthen effective interaction, cooperation, which includes not only the law enforcement sector, but also forensic experts, social workers, the free legal aid system, and public organizations.

There should be a cross-cutting inclusion of a victim-centered approach. It is important to remember about human resources that are being depleted, so we need to think about how to maintain the mental resource.

The second block of recommendations is approaches and internal policies in work. Everyone is talking about unification, standardization of approaches, procedures, documents on needs assessment and more. We need to standardize and at the same time look for approaches to each person, because each person is an individual.

The third block is legislation. Introduction of the institution of a lawyer by appointment for victims of gender-based crimes, expansion of the range of sanctions, the concept of criminal proceedings related to domestic violence, systematicity. These issues are on the agenda and are being resolved.

In the implementation process, it is important to remember that all changes are made by people for people. Therefore, if we proceed from this principle, we will be able not only to formally fulfill the requirements for the implementation of the Istanbul Convention, but also to adopt its spirit and form victim-oriented mechanisms and services.