The history of the Ukrainian women’s movement began with those fundamental principles and ideas around which the concept of Ukrainian feminism began to develop, showing its relevance and continuity in different periods of the life of Ukrainian women. In the mid-1880s of the 19th century, Natalia Kobrynska, the founder of the Ukrainian women’s movement, laid the foundations of a new worldview and positioning of women in society, adapting the latest emancipatory trends of Europe to national challenges. Therefore, she is still rightly considered one of the most interesting European feminists, the first theoretician of Ukrainian feminism, who formulated and embodied its main principles, aimed at the formation of a nationally conscious, educated, socially active woman.

Natalia Kobrynska, 1890s

“The women’s issue has penetrated my soul too deeply,” Kobrynska declared 140 years ago in a letter to Ivan Franko about her preoccupation with modern feminist ideas. She gradually crystallized them in her fundamental journalistic works, which still remain the historical foundation of the women’s movement: “On the Women’s Movement in Modern Times”, “Russian Women in Galicia”, “Married Woman of the Middle Class”, “On the Original Goal of the “Norwegian Women’s Society in Stanislaviv” (all published in “First Wreath”, Lviv, 1887), “Women’s Affairs in Galicia” (collection “Our Destiny”, Stryi, 1893), “Domestic Women’s Crafts” (“Our Destiny”, 1893, co-authored with M. Revakovych), “News from Abroad and the Land” (“Our Destiny”, 1893, co-authored with O. Kobylyanska), “Aspirations of the Women’s Movement” (“Our Destiny”, 1895, 1896), “On Ibsen’s Nora” (“The Deed”, 1900).

What were the main messages to Ukrainian women from Kobrynska? What ideas and slogans of their time formed the basis of Ukrainian feminism? How do these imperatives speak to modern women today?

- The women’s movement is a component of broader socio-cultural struggles.

“The women’s issue reaches further, it embraces all fields in which women as women are oppressed: in the field of social positions, since they are excluded from them, in the field of higher culture, and finally – in the field of law, both public and civil, since this law treats women differently than men” [10:25 – 26].

Nataliya Kobrynska considered the women’s issue in the context of women’s broad socio-political and spiritual aspirations for their own freedom, individual development, and social visibility. She believed that calls for emancipation, which arose from economic conditions, under the influence of European democratic developments, must develop together with other social issues, and not separately, because this would narrow the essence and principles of women’s aspirations. Therefore, the women’s issue, according to Kobrynska, should not be reduced to a narrow understanding of the struggle for equal socio-political rights for women, but should be interpreted in the broader context of deep socio-psychological and cultural-historical changes in patriarchal society.

- Gender equality.

“In general, women have never spoken out against men as such, but only against the social order, the order that made men masters and pushed women into the position of slaves, excluded from the protection of equal rights, even from science and material independence” [9:374].

The idea of equality between men and women was and is the basis of feminism, but from the beginning of the women’s movement there have been myths about “man-haters” and “women’s struggle against men”. Natalia Kobrynska first addressed the issue of gender parity in her “Report at the meeting of the Stanislavov Women’s Society” in 1884, emphasizing: “I declare to men that we can live with them in common thought for a common idea, and do not consider ourselves only as eternal candidates for their hearts” [3]. With this clear statement, she openly polemicized with the anti-feminist theory of F. Nietzsche: “life knows no equality and in itself is nothing other than the insult and appropriation of what is alien and weaker” [12:21]. And since a woman is weaker, it is worth “keeping her under lock and key, as something that is already condemned to slavery by nature and can only have some value in strong hands” [12:21]. Following Nietzsche’s ideas later provoked the emergence of a separate layer of artistic narrative in literature, in which the main motive is “strength and passion”, and a woman is treated only as an element of a “true strong man”. In contrast, Ukrainian feminism from the very beginning consistently affirmed the idea of equality and socio-cultural partnership between men and women. “It must be so that a woman, as a conscious person, stands next to a conscious man” (letter from Natalia Kobrynska to Osyp Nazariev, 1912) [2, F. 13, No. 35].

Ivan Franko, 1896 Mykhailo Pavlyk

Natalia Kobrynska’s ideas were confirmed in the reality of the time: the development of the women’s movement in Galicia was in every way facilitated by authoritative men such as Ivan Franko, Mykhailo Pavlyk, Mykhailo Drahomanov, Panteleimon Kulish, Vasyl Polyansky, who not only with personal support but also with their own works worked out the ideological ground for emancipatory ideas and consensus.

home actively supported women on this path.

- Feminism as humanism.

“Kobrinskaya took into account a woman exclusively as a person, and considered the women’s movement to be the only means at that time for the elevation of this part of humanity” [6:3].

The desire to revive and affirm in a woman, first of all, a person with equal rights and opportunities for personal self-realization was a significant achievement of the emancipatory ideas of the founder of the women’s movement. It is in this context that feminism was consonant with humanism.

- Nationalism and civil responsibility of women.

“A woman has always and everywhere been able to understand the spirit of her time and the demands of her society” [13:328].

The national vector is a unique feature of the Ukrainian women’s movement, which was due to a long period of Ukrainian statelessness and national oppression. Therefore, the idea of Ukrainian feminism from its very inception was clearly based on national principles. The acquisition of an independent status of women in public and family life in the understanding of Kobrinska is consonant with the concepts of national, autochthonous, spiritually rooted in one’s own tradition. Hence the close connection between feminism and nationalism, the identification of women’s emancipation and national liberation struggles, which was especially relevant in the conditions of an imperially divided Ukraine. In the words of Natalia Kobrinska, with the emergence of the emancipation movement, “our women throughout the vast expanse of Rus’-Ukraine felt their national existence,” “our intelligent woman felt herself simultaneously a Ruthenian and a man, and remembered her national and public rights” [8:287] (in the language of that time, the word “Rusyns” was used to designate Ukrainians, and “man” in the meaning of “person.” — Ed.).

In a broader sense, feminism was also associated with a state-building strategy, in which women were assigned the constructive mission of a creative citizen, because, as Kobrynska believed, “women took an active part in all the great evolutions of human development” [14:325]. Responding in a timely manner to the national-patriotic challenges of the era, the “spirit of women” and their civic intuition were harbingers of historical transformations and indicators of the life of the people.

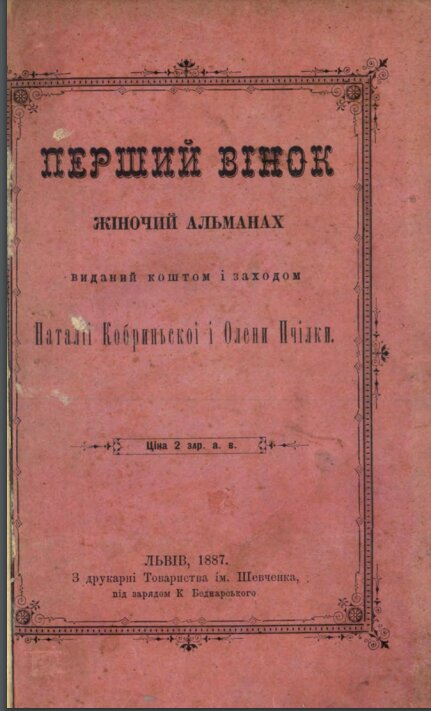

Under the slogan of national unity, the women’s almanac “The First Wreath” was published in 1887, proclaiming the main slogan of the publication: “In the name of our national unity.”

Later, in the interwar period, the national idea became central to the ideology of the Ukrainian women’s movement, and was clearly expressed in the journalism of Milena Rudnytska: “Service to the Nation was and is one of the leading ideas of the Ukrainian women’s movement, from which it draws its ethos and its ultimate justification” [16:201].

- Feminism, European Integration, and National Identity

“The so often praised Europeanism should not consist in subordinating our spirit to a foreign country, in neglecting everything that is our own, but rather in the ability to elevate ourselves, our own and our national individuality to the heights of European culture and art. And we will never achieve this without learning to preserve the features of our specific character, without learning to truly “be ourselves”” [11:387].

The women’s question arose on the waves of the European progressive movement, associated, in particular, with the change in industrial, socio-economic and cultural relations. Therefore, observing the rapid progress of the women’s movement in Europe, where it had long had its own tradition, literature and achievements, Nataliya Kobrynska sought, on the one hand, to adopt the main trends of European feminism, and on the other – to adapt them to Ukrainian socio-political conditions. “This is quite natural, when we notice how vividly and strongly our society is drawn into its circles by the modern European development of social and economic relations” [8:287], she explained the growing interest in the women’s question in Galicia. It is no coincidence that Kobrynska purposefully projects all her subsequent feminist activities onto Europe, focusing on the European experience of women’s emancipation, primarily in the educational and socio-economic plan, becoming, in the words of M. Bohachevska, “one of the most interesting European feminists” [1:17].

Kobrynska’s unwavering interest in world feminism is indicated by her interesting studies-reviews, which describe the experience and social and legal status of European women, ― “On the Women’s Movement in Modern Times” (“The First Wreath”, pp. 5 – 25); trends in the women’s movement in Europe ― “News from Abroad and the Land” (“Our Destiny”. Stryi, 1893, pp. 79 – 93, co-authored with O. Kobylyanska). Striving, in Frankov’s words, “to involve our women in the sphere of ideas and interests of advanced European women” [17:502], Nataliya Kobrynska initiated the practice of effective cooperation with representatives of other nationalities – Czechs, Poles, Germans, with whom she jointly submitted petitions to the Austrian parliament on women’s educational and electoral rights.

Nataliya Kobrynska popularized European feminism in every possible way, borrowed European stylistic trends in her work, summarized and translated advanced European works and works in order to “introduce the spirit of Europe into Ukrainian relations.” But she perceived the need for Europeanization primarily as an organic

development, the path of formation and self-affirmation of a mature nation while preserving its self-identity in order to expand intellectual horizons. Therefore, Kobrynska advised to assimilate Europeanism in the form of a mental formula – “to be oneself” in all manifestations of national existence: political, spiritual, cultural and historical.

- Woman and literature.

“We set ourselves the goal of influencing the development of the female spirit through literature, because literature was always a true image of the bright and dark sides of the social order, its needs and shortcomings” [13:328].

Almanac “The First Wreath”, published in Lviv in 1887.

The principles of early Ukrainian feminism are closely connected with educational and intellectual slogans, with the attempt of women to declare themselves through their own writing. “I came to understand the position of women in society through literature” [7:322], Kobrynska explained the origin of her emancipatory ideas. After all, with her own feminist works, the writer formed a new reading for Ukrainian women, striving to give her sisters exactly the book that would show a different essence of women through concrete life examples and women’s destinies, emancipate their multifaceted personality, and encourage them to take an active social role. It is no coincidence that the goal of the first Ukrainian feminist organization, the “Society of Russian Women,” founded in 1884 in Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk) by Natalia Kobrynska, was the slogan “awakening the female spirit through literature.” Initially, it was planned that it would be a women’s reading room with its own publishing house, created for literary purposes. Why did literature become the most effective way of representing women then? In the conditions of Ukrainian statelessness, when the press and Ukrainian parliamentarism were silent, when a shameful linguocide was taking place in the Dnieper region, writing became an important resource for self-realization and expression of will, a sign of the people’s intelligentsia. According to Kobrinska, “in times of political unfreedom, literature is a kind of refuge for freedom” (letter from N. Kobrinska to Ivan Beley dated September 11, 1885). Also, through literature, a woman could become spiritually liberated, express her feelings and needs, and express herself in writing.

Olena Pchilka and Natalia Kobrinska – co-editors and patrons of “Pershy Vinek”

According to the idea of the founder of the Ukrainian women’s movement, it was literature that was to play an important consolidating role, gathering all conscious “women under the banner of literature for the purpose of explaining and uniting thoughts” [13:299]. In a broader state-building and national-historical perspective, literature, according to Natalia Kobrynska, served as a unifying factor for the nation: “Rus-Ukraine, also divided politically, comes together with the help of literature” [13:290]. This was fully demonstrated by the publication of the women’s almanac “The First Wreath”, which initiated the tradition of women’s writing and literary sisterhood and united 17 Ukrainian women writers on both sides of the Zbruch River.

The Almanac “The First Wreath” — a modern reprint

- Woman and War.

“Our capabilities are as small as our environment, but our work is as great as our goals” [6:3].

Natalia Kobrynska, 1910s

Having personally experienced all the hardships of the First World War, Natalia Kobrynska advises passionate Ukrainian women to actively participate in the struggle for national freedom and their own state, and to understand the importance of even the smallest help to the front. The writer suffered morally in this war, becoming the victim of a baseless denunciation with accusations of espionage, barely escaping arrest, remaining alone in the devastated Bolekhov. However, in her civic consciousness, the war events also stirred up optimistic faith in the solution of the Ukrainian question. Already physically and spiritually exhausted, she refused to lead the national liberation leadership in Bolekhov, more willingly devoting herself to concrete work aimed at helping the army: she participated in fundraising and charity missions, made dressing materials for the front, and gladly hosted Sich riflemen who heroically repulsed Bolekhov from the Russian rear in her hut. The writer described all the tragic experience of the war in her military short stories in the cycle “War Stories”, depicting terrible pictures of national martyrology. In these literary texts, the motif of femininity permeates the idea of a viable power of Ukraine, capable of raising triumphant life over the victims of death. In the works of Natalia Kobrinskaya, the idea of saving the nation is feminine in its essence.

- The conflict between motherhood and civic mission.

“…In order to bring my idea to life, I renounced the happiness that motherhood gives!” [4:6].

According to Olga Duchyminska, Natalia Kobrynska tried to “give new goals and values to the female soul” [5:15], to affirm the “individuality of the female spirit” whether in married life or in personal self-realization and intellectual development. Kobrynska considered the defining value of a woman to be her moral dignity (“purity”), which was most valued at all times: “I consider those women who preserve [protect] purity to be the healthy nerve of society, which preserves the human race.