Atlanta 1996. I’d long wanted to rewatch those Olympic Games — my first viewing, when I was only three years old, had long faded from memory. Then, during the quarantine, the Olympic Channel decided to delight fans by uploading full recordings of the Games on YouTube, including gymnastics — which, in my personal universe of priorities, is a definite must watch. Not only because of our own Lilia Podkopayeva, but also because of the Magnificent Seven, as the U.S. women’s gymnastics team was famously called.

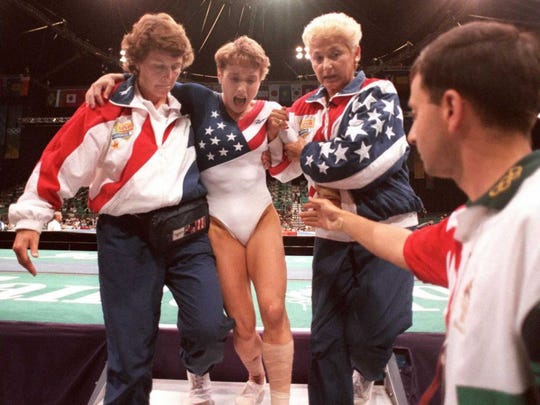

Even knowing in advance who won the team final, I still got immense joy from those old broadcasts — until the very last vault. That was when I remembered what would happen next, and who would inevitably appear on screen. In a moment, Kerri Strug would injure her leg, and team doctor Larry Nassar would rush to her aid.

The same doctor who would later be exposed as a pedophile, who had already been abusing gymnasts — even back then, in the 1990s.

It was the first of four Olympic Games where Larry Nassar worked with the U.S. gymnastics team. His abuse went unpunished for two decades after Atlanta — and had already been happening for almost ten years before it.

In 2017–2018, Nassar was convicted of possession of child pornography (60 years in prison) and of ten counts of sexual assault against minors — receiving 175 years for seven of them and an additional 40 to 125 years for the remaining three. The “ten” counts refer only to the official verdict. In reality, as of early 2020, Nassar had raped at least 517 girls and women over the span of three decades — those who found the courage to come forward.

On June 24, Netflix released a documentary about this largest harassment case in sports history, titled “Athlete A.” The previous year, HBO had released another documentary on the topic — “At the Heart of Gold: Inside the USA Gymnastics Scandal.”

The Nassar case was not the first, nor the only one — but it became a turning point. At the very least, public discussion and awareness of harassment in sports grew dramatically. Real systemic change will still take time, but the fact that the athletic community is now breaking the silence, acknowledging the problem, and ruthlessly (though not always consistently) removing abusers is already a major step forward.

According to ChildHelp statistics,[1] 40–50% of athletes experience some form of abuse, and 2–8% face sexual abuse. Research by the Council of Europe within the Start to Talk initiative[2], aimed at protecting children from violence in sports, shows that one in five children experiences sexual harassment. Meanwhile, data from INSPQ[3] indicate that 98% of child harassment cases are committed by coaches, teachers, or instructors.

Causes: An Atmosphere of Fear and Manipulation

Undoubtedly, the number one cause is the perpetrator. But why is sports such a fertile ground for their abuse?

First of all, because the word “violence” is still often used almost interchangeably with the word “sport.” This is especially true in elite sports, where constant competition, pressure, and the chase for medals prevail. When athletes live under constant emotional and physical strain, they become accustomed to it and may no longer recognize it as harmful.

Yelling, insults, and physical blows are still treated as “normal” — a supposed part of “discipline.” While the global sports world is trying to move away from such methods, they remain widespread across post-Soviet countries, where coaches who began their careers in the USSR — or those trained in that system — still dominate. Progressive voices advocating for change remain a small minority.

Sexual abuse is often preceded by psychological and physical abuse. The perpetrators may not always be the same people, but a climate of anxiety, fear, and normalization of pain creates the perfect ground for adding yet another layer of harassment — another “sacrifice on the altar of sport” in the pursuit of Olympic glory.

Another reason is isolation and lack of awareness.

Athletes spend most of their time inside a closed “sports bubble” — surrounded by people who share the same routines, beliefs, and norms. This community develops its own version of “normal,” and unless someone steps outside that bubble and compares experiences, they may not even realize that what they consider ordinary others see as toxic.

Children are the most vulnerable in this environment. Many simply don’t know what sexual abuse is because no one has ever explained it to them. From an early age, young athletes get used to the idea that their bodies don’t belong to them — everyone touches them, whether they want it or not: parents, relatives, coaches, doctors. Some of these touches can be painful or uncomfortable, making it difficult for a child to distinguish between what’s medically necessary and what’s inappropriate.

Only now is society beginning to understand the importance of sexual education and respect for personal boundaries, especially when it comes to children.

And one of the main reasons: respect — and fear — of authority.

For many, going against a coach or a senior official is unthinkable. The old mentality of “the coach is the law” still dominates. Their authority is rarely questioned, and they are often supported by other influential colleagues.

However, abusers are not always openly aggressive. A common manipulative tactic is “grooming” — masking abuse behind care and affection. Such individuals can appear kind, attentive, and charming: they flatter their athletes, bring treats forbidden by other coaches, joke with them, show interest in their lives, and win the trust of parents. This duality confuses children and teens, leading them to doubt their own perceptions: “Maybe they’re not that bad — maybe I misunderstood.”

And for outsiders, it becomes even harder to believe that such a seemingly kind and friendly person could be capable of violence.

All these factors appear again and again in almost every new case of harassment in sports.

And revisiting these stories — starting with Larry Nassar — is necessary.

Netflix, surely, won’t mind the reminder.

“How Much Is a Little Girl Worth?” — A Turning Point in Gymnastics

Larry Nassar took root in sports medicine early in his career — in 1978. Over the years, he rose to become chief physician of the U.S. women’s gymnastics team, which he joined in 1986, and worked as an osteopathic doctor at Michigan State University (MSU) and other athletic clubs and schools. For 18 years (until 2014), he served as the national medical coordinator for USA Gymnastics (USAG) — the governing body for artistic, rhythmic, acrobatic, trampoline, and other gymnastics disciplines. In other words, Nassar had access to and influence over the entire medical system of American gymnastics.

Most of his assaults took place either in his office or at his home, where he offered some athletes “private treatments.” During competitions — including the Olympic Games — he would invite gymnasts to his hotel room. After performing legitimate medical procedures, Nassar would proceed to what he called his “special treatment methods”: inserting his fingers into their vaginas and anuses, touching their breasts, masturbating in the corner or even in front of the athletes. He often managed to assault girls in the presence of their parents, positioning himself so they could not see exactly what parts of the body he was touching.

Reports of Nassar’s abuse — both oral and written — had been sent to USAG leadership and individual clubs for decades, but action was only taken after 2015, when Sarah Jantzi, coach of gymnast Maggie Nichols, filed a formal complaint. Jantzi overheard her student discussing Nassar’s “treatments” with a friend and later discovered that the doctor had been sending Maggie inappropriate messages and compliments about her appearance.

That report finally led to Nassar’s dismissal from USA Gymnastics. Michigan State University followed suit only in 2016, after the allegations gained national attention.

“1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2004, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 — these are the years when we spoke out about Larry Nassar’s abuse.”

That’s how Olympic champion Aly Raisman began her speech when she and other survivors received the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYs. Later it became known that reports had been filed even before 1997.

“All those years, we were told: ‘You’re mistaken. You misunderstood. He’s a doctor. It’s normal. Don’t worry, everything’s under control…’ The greatest tragedy of this nightmare is that it could have been prevented. Predators thrive on silence… All we needed was one adult — just one decent adult — brave enough to stand between us and Larry Nassar,” Raisman said.

The voice that was finally heard belonged to Rachael Denhollander — a lawyer and former gymnast who, in September 2016, told her story to The Indianapolis Star. Alongside her was the anonymous “Athlete A,” who later turned out to be Maggie Nichols. Their testimonies became the basis of the documentary “Athlete A.”

Nassar began abusing Denhollander when she was 15. She had come to him for treatment of back pain.

“Each time I lay on that table, trying to make sense of what was happening, I knew three things,” she said in court.

“First, it was clear Larry did this regularly. Second, I was certain that some women and girls must have reported him to MSU or USAG officials. Third, I believed that if they knew what he was doing and hadn’t stopped him, then his treatment must have been legitimate. The problem had to be me, I thought. So I kept lying still. I didn’t know it then, but I was right about the first two.”

In 2016, Denhollander not only spoke publicly but also filed a police report with extensive documentation: legal analyses of Michigan statutes, medical evidence of how pelvic floor therapy should actually be performed (a procedure Nassar used as cover), witness statements, expert lists, and personal journals describing her trauma — which Nassar himself read as part of the case file.

“Did the leadership of USA Gymnastics and MSU expect this level of preparation from children before believing them?” the article asked rhetorically.

Even this wasn’t enough for Michigan State University to take the accusations seriously — the institution initially sided with Nassar. One physician, Brooke Lemmen, testified in his defense, claiming there had been no penetration and suggesting the girl had “misinterpreted what happened,” saying:

“When you’re 15, you think everything between your legs is your vagina.”

Similar responses were given to other girls who tried to report the abuse.

Three months after Denhollander’s story broke, Nassar was arrested. The FBI later found over 37,000 child pornography images and videos in his home — including footage of himself assaulting minors.

Over the following year, more and more athletes came forward to share their traumatic experiences — and to expose the complicity of USA Gymnastics and MSU, which had ignored the abuse happening under their watch.

Nassar wasn’t the only predator protected by USA Gymnastics. The organization had ignored complaints about William McCabe and over 50 other coaches. Some weren’t even banned — they continued working with children. McCabe was finally arrested in 2016, after a gymnast’s mother reported him directly to the FBI.

Olympic champion McKayla Maroney revealed that USA Gymnastics paid her $1.25 million to keep silent about years of abuse by Nassar.

“It started when I was 13 or 14,” Maroney wrote in her victim statement.

“It seemed like whenever and wherever he had the chance, he ‘treated’ me — in London before we won Olympic gold, before I earned silver there. The worst night of my life was when I was 15. We were flying to Tokyo, and he gave me a sleeping pill for the flight. The next thing I remember, I woke up alone with him in his hotel room — and he was ‘treating’ me. I thought I was going to die that night…

People need to understand that sexual violence doesn’t happen only in Hollywood or Congress — it happens everywhere. It seems that wherever there’s power, there’s potential for abuse. I dreamed of the Olympics, but what I had to endure to get there was unjustifiable and disgusting.”

When court hearings began in January and February 2018, the number of survivors wishing to speak skyrocketed. Instead of the planned 88 statements, the court heard 204 testimonies over nine days — some in person, others in writing.

Many said they found the courage to speak after watching the first brave women confront Nassar in court. One mother read a statement on behalf of her daughter, who had taken her own life after years of depression and trauma. Another father asked the judge for permission to have “five minutes alone in a locker room with this demon” before attempting to lunge at Nassar — stopped only by security.

After one particularly emotional day, Nassar asked the court to stop hearing testimonies, claiming they were “too hard to listen to” and accusing the judge of turning the process into “a media circus.”

Judge Rosemarie Aquilina denied his request.

The last to speak was Rachael Denhollander, whose rhetorical question became symbolic of the entire trial:

“How much is a little girl worth?”

“When Larry was sexually aroused — when he found pleasure in our pain — his actions were evil and wrong,” she said.

“I ask you to render a judgment that shows what happened to us matters. That we are worth everything — the fullest protection the law can give.”

Consequences of the Nassar Case: Legal Reforms and an Overburdened System

The punishment of Larry Nassar himself did not mark the end of the case. Lawsuits flooded in against USA Gymnastics (USAG), the U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC), the Twistars Gymnastics Club, and Michigan State University (MSU). The entire leadership of USAG — including President Steve Penny — resigned (albeit reluctantly, under pressure from the USOC), as did MSU President Lou Anna Simon. Penny was later arrested on charges of evidence tampering, while Simon faced charges of providing false information to police.

USAG also suspended John Geddert, head coach of the 2012 Olympic team and owner of Twistars — a close friend of Nassar, known for his aggressive and abusive training methods. One gymnast testified that Geddert once witnessed one of Nassar’s “treatments” but simply left the room after making a joke.

In 2018, the Karolyi Ranch — the U.S. women’s gymnastics national training center founded by Béla and Márta Károlyi in 1981 — was shut down. It was there, many athletes later said, that the conditions most conducive to Nassar’s abuse were created. Parents were forbidden access, gymnasts lived under a climate of fear and bullying, trained through injuries, and developed eating disorders due to extreme dietary restrictions. Trust was nonexistent. Many survivors claimed that the Károlyis knew about Nassar’s actions, though the couple denied all allegations. Investigations into their role are still ongoing.

The biggest systemic change came with the passage of the Protecting Young Victims from Sexual Abuse and Safe Sport Authorization Act of 2017. The law requires sports organizations to report all suspected abuse directly to law enforcement and led to the creation of the U.S. Center for SafeSport, an independent body tasked with investigating and preventing emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in American sports. The center also develops training programs and educational materials on athlete safety.

However, the initiative quickly revealed serious underfunding issues. SafeSport receives an average of 230 new complaints per month, but lacks the staff and resources to handle them all. With a team of 40 employees — 24 dedicated to case management — the center was handling 1,200 active investigations as of early 2020. SafeSport’s first CEO, Shellie Pfohl, resigned in 2019, citing inadequate funding. Her successor, Ju’Riese Colón, continues the work.

As of 2019, SafeSport’s annual budget was $11.3 million, twice what it started with, funded primarily by the USOC and national sports federations. This dependence has raised questions about its true independence, since SafeSport is tasked with investigating the very organizations that finance it. The only government funds it receives are small grants for educational initiatives.

In its first three years, SafeSport sanctioned over 600 individuals accused of various forms of abuse. Yet these numbers don’t reflect the full picture — in several cases, courts overturned or reduced lifetime bans, including those against figure skating coach Richard Callaghan, taekwondo athletes Jean and Steven Lopez, and weightlifter Colin Burns.

Meanwhile, investigations into the institutions that enabled Nassar have dragged on. In February 2020, the USOC and USAG offered $215 million in settlements to Nassar’s survivors in exchange for dropping lawsuits — a move that would effectively shield both organizations and individuals like Penny and the Károlyis from liability. Gymnasts including Simone Biles and Aly Raisman condemned the proposal as an attempt to bury accountability ahead of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics (later postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

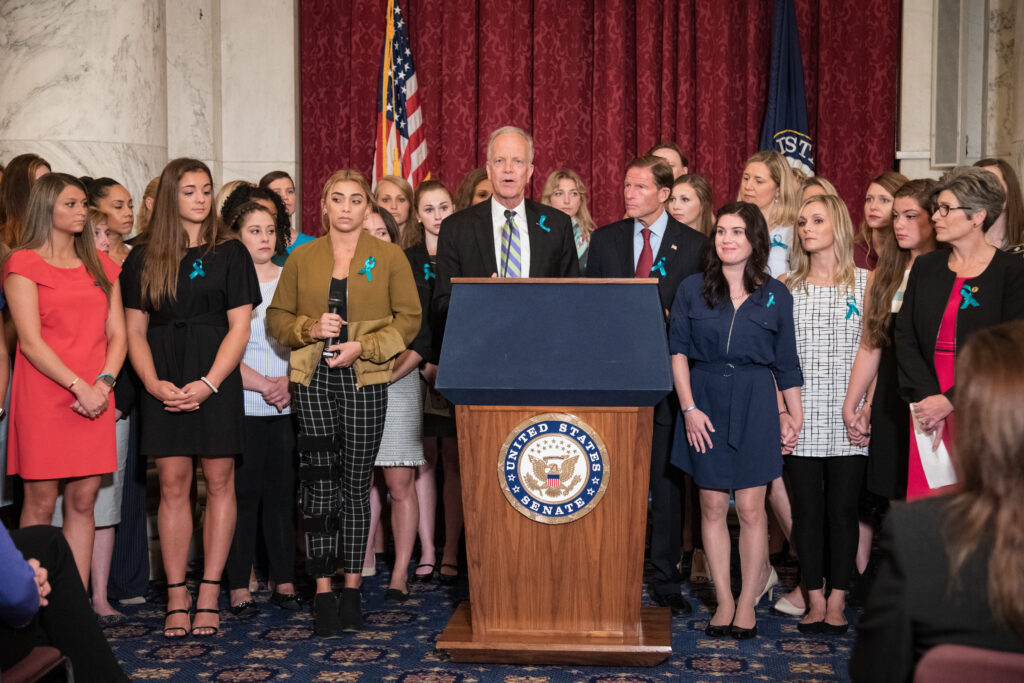

A 2019 U.S. Senate report by Jerry Moran and Richard Blumenthal concluded that the FBI, USOC, USAG, and MSU had all the necessary evidence to stop Nassar at least a year before his arrest. The report also proposed new legislation to expand protections for athletes, empower Congress to dissolve the USOC and Paralympic Committee if necessary, and increase SafeSport funding to $20 million per year — a measure still under consideration.

The campaign for its adoption is now being actively led by three-time Olympic swimming champion and human rights advocate Nancy Hogshead-Makar, who herself survived rape at the age of 19. Today, the former athlete heads the organization Champion Women, which advocates for safe sport, gender equality, and the elimination of discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community. Hogshead-Makar supported the creation of SafeSport and collaborates with Child USA, which fights against child abuse.

In general, according to the SafeSport database, at the time of writing, 1,235 sports professionals had been temporarily or permanently suspended for various forms of abuse. The most bans are in gymnastics (227), swimming (186), and hockey (117). And if the imbalance in cases of violence committed by men surprises or unsettles you, note that in gymnastics, where there are the most cases, 219 of the suspended individuals are men and only 8 are women. This is partly because the vast majority of coaches and sports administrators are still men. According to the International Olympic Committee, at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics, 89% of accredited coaches were men.

SafeSport’s rulings date back to the early 1980s and apply only to the United States. It is also important to note that professional sports leagues such as the NBA/WNBA and the NFL are not under the center’s jurisdiction.

Other cases: inspired by the fall of untouchables

The example set by American gymnasts and the #MeToo movement, which peaked during the Nassar trial, inspired other athletes to speak out about the violence they had experienced.

For Belarusian four-time Olympic champion of the 1970s Olga Korbut, this became a reason to speak again about how her coach Renald Knysh raped her. Korbut first spoke about it in 1999, saying she had felt like a “sex slave.” She was supported by gymnasts Halyna Chesnovska and Liudmyla Riabkova, who were also harassed by the same coach. In an interview with Radio Svoboda, they recalled that after training, Knysh would drive the girls home, and the one he left for last he would take into the forest and rape. During training sessions, he often made sexually suggestive jokes and showed porn magazines and sex toys. They said that everyone knew about it and called them “Knysh’s harem,” but nothing was done to stop it. The girls didn’t tell their parents because they felt ashamed, and the coach was considered an authority figure — if they wanted to compete, they had to obey. Knysh, who died last year, called the accusations slander but also said that it was “natural” for gymnasts to be “fond of their coach” and that each “wants to become his lover or wife.”

Ukrainian Olympic champion and gymnast Tetiana Hutsu, who now lives in the United States, also spoke out about abuse. According to her, in 1991, when she was 15, the then 19-year-old Belarusian Vitaly Scherbo raped her in a hotel room and ordered her not to tell anyone. Tetiana said that she tried to talk to Vitaly about the incident in 2012 but did not receive an apology. Scherbo sued Hutsu for defamation, arguing that “the greatest athlete in the history of sports” could not be “so mentally unstable and insane as to do such a thing.” The conflict ended with Hutsu and Scherbo agreeing not to comment on each other in the media.

Former American football coach Jerry Sandusky is serving a sentence for at least 45 cases of sexual abuse of underage boys. This story occurred before Nassar’s and is very similar to it. Sandusky’s victims were participants in The Second Mile — a charity organization he founded at Pennsylvania State College to support underprivileged teenagers and, according to its slogan, to give them “hope.” Even Sandusky’s own son was among the victims. As in the Nassar case, reports about incidents began surfacing long before a full investigation — as early as 1998 — but the university’s leadership covered them up. Later statements revealed that the abuse had been happening since the 1960s. Sandusky was imprisoned only in 2012. He has never admitted his guilt and has tried to obtain a retrial.

A series of harassment allegations has also reached the U.S. national swimming team. Last week, six more athletes filed lawsuits against USA Swimming, claiming that the federation’s leadership knew about the abuse by former coaches and did nothing to stop them. The swimmers said they had experienced harassment from Mitch Ivey and Everett Uchiyama — both already removed by the federation but still free — and from Andrew King, who is currently serving a prison sentence for pedophilia. Suzette Moran stated that the abuse by Ivey began when she was 12, and shortly before the 1984 Olympic trials, the 17-year-old Suzette became pregnant by her coach, who forced her to have an abortion. Years of rape led to depression, panic attacks, and destroyed her love for swimming. Earlier, coach Sean Hutchison received a lifetime ban from USA Swimming after being accused of harassment by world champion Ariana Kukors Smith.

Although American cases often become the most high-profile and make global headlines, the problem is by no means limited to the United States. Shortly after the first public statements about Nassar’s abuse, the issue of child sexual violence emerged in British football. The scenario was the same: it had been happening for a long time, at least since the 1970s. Thanks to the large number of people who came forward to tell the truth, within a year and a half 300 coaches and scouts suspected of abuse were identified across 340 football clubs in the country. In total, 12 people were imprisoned. Michael Carson committed suicide before his trial began.

New accusations were brought against coach Barry Bennell, who worked with youth teams at Crewe Alexandra and Manchester City and had already served three prison terms in the United States and the United Kingdom for raping minors. Colleagues called him a “star maker” and admired his ability to spot potential football talents. Bennell, meanwhile, exploited the dreams of young players, promising that “relationships” with him would help their careers. More than a hundred boys suffered from his abuse.

Continuing with football: last year, FIFA permanently banned the president of the Afghanistan Football Federation, Keramuddin Karim, from all football-related activities. This was due to sexual harassment, physical violence, and threats against members of the women’s national team — in addition to the already deeply negative societal attitudes toward women who play football. Many athletes were afraid to speak out about what was happening, as extramarital sexual contact in Afghanistan can be punishable by death. Moreover, Karim threatened to kill their relatives and spread rumors that they were lesbians, which is also extremely dangerous in that country. The athletes reported the abuse anonymously to The Guardian, fearing for their families’ safety. They also said that Karim had a secret room at the federation’s training base where he lured female players, and which could only be opened with his fingerprints.

Heads also rolled in figure skating — particularly in the French national team. At the end of last year, suspicions arose that world championship medalist Morgan Ciprès had harassed a minor skater who trained on the same rink. The girl and her parents said that the French skater sent her photos of his penis (according to USA Today journalists who reviewed the messages, the photos came from Ciprès’s verified Instagram account), while coaches John Zimmerman and Silvia Fontana intimidated the girl, urging her to stay silent because Ciprès and his partner Vanessa James were preparing for the Olympics. They also blamed the victim, saying she was “a pretty girl, and men have needs.” Moreover, the girl’s parents said that another coach, Vinny Dispenza, forced her and another student to message Ciprès asking him to send intimate photos in exchange for pizza from Dispenza himself.

The scandal also led to the resignation of Didier Gailhaguet, the controversial president of the French Figure Skating Federation, who had previously been involved in corruption scandals. Gailhaguet called Ciprès’s actions “stupid” and later resigned over his own misconduct. It later emerged that Gailhaguet had for years covered up sexual abuse by coach Gilles Beyer. Among Beyer’s victims were Hélène Godard and world championship medalist Sarah Abitbol, who wrote about the abuse in her autobiography. Both were minors at the time.

Last year, after a wave of reports about numerous cases of abuse — especially in short track — South Korea launched a large-scale investigation into sexual harassment in sports. Two-time Olympic champion Shim Suk-hee and several other short track skaters accused Cho Jae-beom and other coaches of sexual and physical violence. Cho was sentenced to 18 months in prison for assaulting Shim but denies the rape allegations. “If I criticize my coach, my career is over. If I accuse him of crimes, I won’t get into university or a professional team. That’s how it works,” an anonymous athlete explained in an interview with CNN. Olympic short track champion Lim Hyo-jun was found guilty of sexual harassment, and a month ago, Olympic judo silver medalist Wang Ki-chun was arrested.

The Beginning of Change: Breaking the Silence in Ukraine

And what about Ukraine? For a long time, it seemed that there was complete silence about sexual harassment in Ukrainian sports. Yet a significant — if grim — step forward came with a recent scandal in the climbing federation. Not because it was positive, of course, but because people finally began to speak publicly, pointing out problems and naming those responsible.

Last year, climber Pavlo Vekla stated that when he was a minor, he had been harassed for years by his coach Artur Pechiy. “In Germany, children are taught in school what pedophilia is. And if there’s even the slightest hint — they go to their parents and file a police report,” said Pavlo, who now lives in Germany. “Unfortunately, in Ukraine, it’s different. I only learned the word many years later, when I was already at university.”

At the beginning of 2020, Vekla was supported by his teammates — seven athletes, including team leaders Danyil Boldyrev and Yevheniia Kazbekova. They collected testimonies[14] in which they described in detail their experiences working with the coach and succeeded in having him fully dismissed from the federation, where he had remained vice president and continued coaching even after his official suspension from coaching activities.

Pechiy’s students experienced psychological abuse, blackmail, restrictions on personal life, extortion, inappropriate training loads, and neglect of safety regulations that led to injuries. According to Fedir Samoilov, Pechiy massaged boys and touched their genitals “because it was more convenient for him,” or “inserted a finger into their anus.” He also “asked the boys ten times a day when and how often they masturbated,” gave them advice on how to do it, and described how he did it himself. Samoilov had previously supported the coach but changed his opinion after re-evaluating his experience and publicly apologized to Pavlo Vekla.

Climbers had reported Pechiy’s behavior to the coaching council earlier — back in 2013 — but according to Vekla, “they were only laughed at.” Pechiy himself, predictably, called it all lies and a publicity stunt and filed a counterclaim.

After all these stories, it may seem that sport is an all-powerful evil and a source of inevitable danger. The problem is indeed far from being solved: such a deeply entrenched system is difficult to dismantle in a year or even several years, no matter how powerful the effect of these sporting “Weinsteins.” Moreover, trust in law enforcement remains weak, and not all parts of society are mature enough to discuss and take this issue seriously.

However, it is important that — however slowly — we are beginning not only to see this problem but also to understand and respond to it. The only way to protect ourselves and our children who play sports is to speak out. Speak about our own experiences, speak about the experiences of others. Overcome discomfort and talk to children about their bodies. Overcome fear and shame and talk about the violence we have experienced or witnessed. Support the broad implementation of sexual education in society.

Ukraine does not yet have its own equivalent of SafeSport, but regardless of the field in which violence occurs, you can contact the police or civil society organizations specializing in this issue, such as La Strada Ukraine.

Leave a Reply