Humor is a very important socio-cultural element of our everyday life. It reflects the prevailing mood, reaction to certain events, attitude towards them. With the help of humor, we talk about everyday life and distract ourselves from it. The famous quote by Les Poderviansky: “Ukrainians often laugh at themselves — this is a sign of mental health.”

We are used to talking about Ukrainian humor and especially the sexism in it in the modernity of the already independent Ukraine — with the flourishing of television shows and humor in magazines and newspapers. And this is quite fair, but in fact certain manifestations can be traced much earlier.

Ukrainian humor and folk traditions.

Ukrainian humor is rooted in folk traditions that reflected the stereotypes and gender roles inherent in that time. Women acted as objects of jokes and laughter, often in connection with their family status and/or role in the household. The specifics of humor of each people are determined by its worldview, and Ukrainians are no exception.

Much information can be gleaned from folklore: folk songs and legends, proverbs and superstitions. An equally interesting source of information is the collection of anecdotes published in 1899 by ethnographer Volodymyr Hnatiuk. This is one of the most complete collections of that time, from which one can draw conclusions about what was considered funny. An entire section in the collection is devoted to women and is called “Women”[1].

There is nothing in such collections that was considered wrong in the realities of that time. A woman is stupid because she is a woman. A woman can only do household chores because she is a woman. This is the norm of that time and sexism today.

Women in folk anecdotes, legends and fables appear in typical roles – wives, mothers, housewives: “The girl carried water with a jug from the cistern”; “A vigilant hostess”; “A young man came to woo a woman’s maid”; “A stepmother came to look after other people’s children and cooked a full pot of porridge.” Traditionalism is no different: women are depicted as housewives, responsible for household chores and the family, men are shown as the main owners, a leading figure in work or public affairs.

A woman’s inability to manage the household was ridiculed, and a man’s manifestation of power over her was welcomed. There is, for example, such an “anecdote.”

It is interesting that even despite the low respect for women, the 1899 collection includes feminine nouns: “strong woman,” “doctor,” “spinning woman,” “young woman,” etc. This suggests that feminine nouns are inherent in the Ukrainian language, they are recorded both in the vernacular and in historical literary sources.

Stereotypical, traditional attitudes towards women were the norm – other roles were not considered possible in principle. Humor as a reflection of the state of society also did not provide an understanding of gender inequality or sexism, so female images were often objects of jokes and laughter. Women were portrayed as careless, stupid, and unable to do anything without a man.

The humor and satire of that time focused mainly on political phenomena, so it is difficult to systematize jokes about women, but several stereotypes can be distinguished.

A woman – a mistress, a prostitute or a “walking problem”?

Everything is clear about the woman-mistress: this image was mainly used in jokes, either ridiculing a woman’s skills and her household chores, or this image ruled in the background – a woman was a secondary heroine of a funny story about a man and his antics or about children. The image of a “walking problem” was often repeated here: although a woman had many tasks that she solved independently, most often a man was equally positioned as the one who knows better and whose word is decisive.

From the second half of the 19th century, sorority folklore began to be recorded. The largest collection of it was left by Khvedir Vovk. True, not only women but also men were ridiculed here. The humor is very reminiscent of today’s: the size of the genitals, the number of partners were considered funny. At the same time, sexual relations were not considered something dirty, and Ukrainian folklore contains a lot of information about how our ancestors made love. A woman who had many sexual partners appeared as a funny figure, not always ready for marriage and “open” to everyone. A man with the same number of partners was criticized at most mildly for being unpretentious, but was not particularly ridiculed.

Watching modern humorous TV shows, one gets the impression that nothing has changed since the 19th century. A woman is also portrayed as a housewife who constantly makes scandals with her husband for the mess at home and waits for March 8 as her only day off; women are also ridiculed, calling them easily accessible, commenting on their figure, sexual preferences or number of partners; it is also considered funny to show that a woman does not know how to do anything and cannot do anything herself: neither drive a car, nor do repairs, nor plan, nor decide.

Soviet satire – about sexism or equality?

The position of women in the Soviet Union is a separate big topic, which often becomes the subject of heated debate. On the one hand, equality was supposedly achieved: women in production and construction of factories, in war and in everyday life. In reality, equality was only declared, not fixed, because while men were in the factory, women were in everyday life and in the factory. The reproduction did not disappear anywhere The role of the mother was elevated to the highest level in the USSR. Such a division could not but affect humor as a reflection (and often a construction) of reality.

Satire and humor in the USSR were assigned the role of a “party weapon”. Soviet newspapers and magazines relied, on the one hand, on caricatures, feuilletons and humorous stories, which were more entertaining than serious. On the other hand, these genres were based on typical recognizable images, because the laughing effect was achieved precisely at the expense of recognizability.

Read more about this in the article by Katerina Yeremeyeva “Worker, Victim, Consumer: Female Images in Soviet Satire”

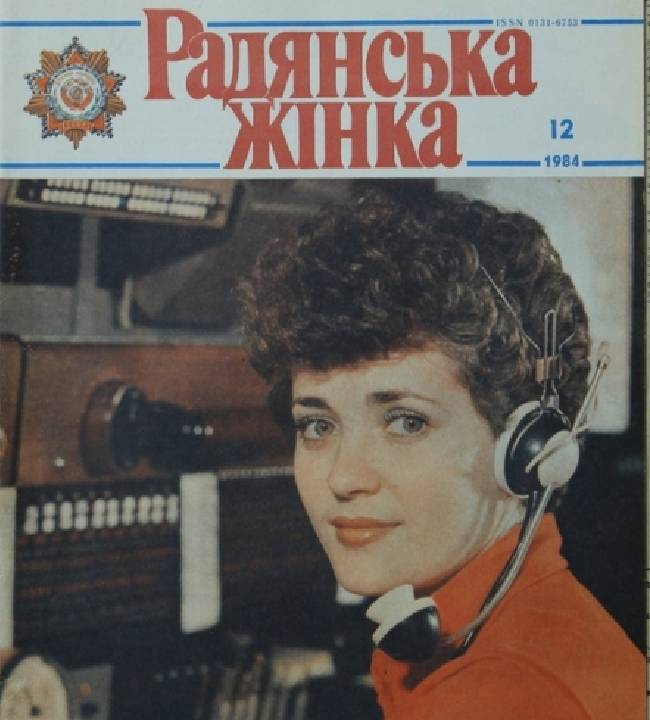

Periodic publications exploited typical images. A woman had to be a conscious citizen of her state, obey the authorities, be a patriot, understand world events and evaluate them accordingly. At the same time, she is the guardian of the home: her house is clean, her children are well-groomed, dinner is ready, and the woman herself is a skilled housewife and a faithful wife. She must look good – an athletic, toned figure is in fashion, clothing patterns and makeup tips were printed for her. That’s her, the ideal Soviet woman.

Magazines and newspapers, and even folk art, are isolated sources of humor. Most of it is political and strictly prohibited, because the Soviet authorities perceive it as agitation and propaganda. Of all the jokes that have come down to us, it is difficult to determine which of them is Ukrainian humor: some jokes exist in different languages, others exist in a bunch of variants in different territories. It is impossible to trace the history of their distribution and say for sure that such and such jokes were created by the Ukrainian people. The information was not recorded, because from the beginning of the 1930s, a joke could lead to 2 years in prison, and in 1935 this term was increased to 3 years. Any jokes, especially if they criticized the authorities, social roles, ridiculed stereotypes or certain groups of people, were considered discrediting the authorities. In 1937, unsuccessful jokes could lead to execution. All this did not contribute at all to the creation of jokes or their dissemination. Of course, jokes existed, but they were passed on from mouth to mouth or presented in a mild form in the text.

The most famous representative of Ukrainian Soviet humor, Ostap Vyshnya, also chose mainly political topics for jokes, ridiculing the authorities and certain human flaws through images of animals or random passers-by. He also used images of women – mainly wives and housewives. Sexism? It seems so, but it should be borne in mind that humor reflects the cultural context and what is unacceptable today can be considered in a different historical context.

However, this does not mean that today we should perceive such humor as the norm, saying that there are women who drive poorly, and there are blondes who do not understand anything. Isolated cases do not characterize a group of people, and our task is to respond to sexism in humor.

Is modern humor a stronghold of sexism?

The situation is changing greatly when it comes to modern Ukrainian humor. Just as in the past, political and social themes remain the main ones, but humor on everyday topics is in full swing, and sexism in it (mainly towards women) is becoming a leading motif.

It is difficult to say whether public humor normalizes sexism, or whether the existence of sexism in society normalizes such humor. The fact remains: sexism exists, and with the development of television and the Internet, it has become ubiquitous.

In 1991, Andriy Danylko appeared on the Ukrainian stage in the image of Verka Serdyuchka. The image became iconic: a certain type of woman began to be called “serdyuchka”.

Verka Serdyuchka is a costumed performance: a man dresses up in women’s clothing. He uses padded breasts, high-heeled shoes, and wigs. The clothes are always flashy.

This resembles drag, a technique of personifying the opposite sex by dressing up in women’s or men’s clothing. However, this is not said and is presented as comedic. Most people identify Verka Serdyuchka first as a comic, then as a musical project. Her lyrics are always everyday, with a twist, she makes fun of herself. The image debuted in the theater, and Danilko gained nationwide fame in 1997 thanks to the humorous “SV-show”.

Literary critic Tamara Gundorova noted in her book “Transit Culture”: “First of all, it is important that Serdyuchka, by her origin, originally personifies the type of an uncultured provincial woman of low social status”[2]. The image of a simple woman from the people seems funny, although it is often used even in politics (for example, Yulia Tymoshenko). Thanks to self-mockery, this does not seem like a problem, although in fact it stigmatizes not only women, but also “nationality” in general, understanding it as provinciality. In Ukrainian humor, the image of “village life” or “village girl” appears.

This type of humor has another negative feature: Verka Serdyuchka speaks either Russian or a recognizable Poltava surzhyk. Later, most of these images of a “simple village girl” are Ukrainian-speaking, and in addition to the moment of misogyny – hatred of women, there is humiliation and ridicule of the Ukrainian language. In particular, because of such humor, Ukrainian began to be associated with something rural.

sly and uncultured. However, again, it is inappropriate to criticize only the image of Serdyuchka as sexist: she is an element in the great history of Ukrainian humor and, as Volodymyr Beglov notes, “she was what, I apologize, we were”[3].

The rapid formation of post-Soviet media culture made possible many phenomena, including television shows and visual clowning. In 1996, “The Weevil Show” was released on screens – an absurd multi-part production with a lot of special effects. The show had five sections: “The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson” (a parody of the Soviet TV series of the same name), “The Residence of Wonderful People” (an absurd retelling of biographies of famous people), “My New Program”, “News with Shendorovich” (news in a funny poetic form), “In Case of a Fire, Call 01” (parodies of social advertising).

No sexism — and this is an important indicator of the new humor of the 1990s. The realm of humor has not yet been explored, television shows are just emerging, and with them a wide audience throughout Ukraine. Sexism is too simple, everyday humor, some minimal manifestations of it on TV are perceived as the norm — everything is like in life.

Leave a Reply